Why I'm Not Fasting on Yom Kippur

As we Jews approach the commandments, first we do and then we year. But what happens when we *don't* hear? And when the mitzvah in question is the Yom Kippur fast?

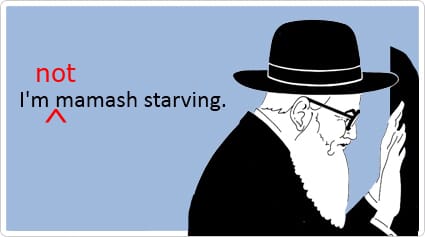

No, I'm really not fasting on Yom Kippur this year. No abstaining from food. No abstaining from water or other liquids. No resorting to halachically (Jewish law-defined) minimum allowable emergency portions. In fact, I intend to eat normally throughout the holiday. No, there is nothing medically wrong with me that would otherwise halachically opt me out of observing the fast. This year, I simply choose not to observe it.

Last Yom Kippur, my shul's famed rabbi emeritus, Herman Schaalman, advocated at our Kol Nidre service passionately--and not a little shockingly--for jettisoning the entire "afflict your souls" element of the High Holy Days on the grounds that Jews have suffered enough throughout history. He suggested turning the Days of Awe, and especially Yom Kippur, into a time of celebrating humanity. I wasn't feeling his message that night, but in truth I've never gotten the point of the tzom--the 25-hour fast--that marks the day for most Jews (even secular ones.)

For the past three years of my Jewish journey, I've tried hard to make sense out of the YK fast, and to perceive my benefit from it. I didn't make it through my first Yom Kippur fast without vomit and cheating. On my second Yom Kippur fast, I staved off the nausea with midday watering. Both times, though, I grasped for meaning (as, if you read them, the above two linked blog posts painfully show.)

I've often wondered why Reform Jews seem to fast so universally. As a denomination we clearly aren't as pious as the fast's seemingly universal nature suggests. After all, we don't see the mitzvot as binding. Our movement is based upon finding one's personal intersection with the commandments, with Jewish ritual, with religious observance. Reform Jews may be very observant in some areas and not in others, and in a synagogue full of us, those areas rarely always match up.

So why do we, as Reform Jews, blindly observe the commandment to fast on Yom Kippur? It can't be simply because the Torah says we'll be "spiritually excised" from our people. After all, if we actually took the bible that literally, we wouldn't be Reform Jews.

So why is it that on Yom Kippur our synagogues overflow with congregants all of whom make it a point to be very visibly, very painfully not eating?

I've asked my fellow congregants and Googled the question for years. The responses I've always encountered I'm sure are familiar to most Jews:

- To take to focus off of ourselves so we can think about others;

- To help is think about those less fortunate around the world who go hungry every day;

- To remove the focus from our bodies so we can think about our actions;

- To remove the focus from our bodies so we can concentrate on repentance;

- To approach death a little bit in order to better appreciate the gift of life; and of course perhaps the most common Reform Jewish answer

- Because we always have--my grandparents did it, my parents did it, so I do it, too.

Yet from a Reform Jewish perspective, in the absence of binding commandments, none of the above responses adequately answers the question of why the Yom Kippur fast is Reform Judaism's biggest--if not only--blind spot. Even as our denominational union underscores that unlike Orthodox Jews we do not take Torah as legally binding, the rabbinical body of our movement suggests that we not make it seem like eating on Yom Kippur is allowable (CCAR Responsum 67) and notes that physical pain is an acceptable part of Yom Kippur observance (CCAR Responsum 151).

One particularly thoughtful answer to the question of whether Reform Jews should fast comes from the About.com Ask the Rabbi page of RebJeff blog Rabbi Jeffrey Goldwasser. In his response, Rabbi Goldwasser notes that there is a counter-intuitive aspect to the way our sages intended the tzom to work. The idea is that in weakening the body by fasting, the ego is broken down as well, allowing one to achieve a level of tesuvha (repentance) that isn't possible when we still feel like we're the ones in control. A beautiful concept, but one that seems to fly in the face of the experience of people like me. If anything, my food-craving body is more ego-centric than usual on Yom Kippur. One tzom doesn't always fit all.

Everything else we personally struggle over, yet try as I might to uncover real debate on the matter, what little there is to find on the Internet about fasting vs. not fasting pretty much boils down into two categories: people writing apologetically about not fasting for medical reasons; and people responding to questions about why one should fast with, essentially, four words--"Because you have to."

So the Yom Kippur fast--and its physical arduousness--even we Reform Jews do not dare to question. Our most tenuously affiliated members come to crowd our sanctuaries and engage in what may be one of the only two religious things they reliably do all year (besides attending a Passover seder). Although we all have a right to our particular style and level of observance--including non-observance--still, they fast.

Yet there is no doubt that some of the people overflowing Reform shuls on Kol Nidre and Yom Kippur day are not observing the fast, even without the "approved" excuses of being too young or having a medical reason to eat and drink. Some people are a little too chipper by mid-afternoon. And some people don't come back later in the day. Some of these people are eating. So why do none of them talk about it? I suppose this is where that spiritual excision is truly at work--what an embarrassment, what a shonda! I think most Reform Jews who don't fast are, simply, shamed into not talking about it.

And how many of us don't fast? Since we don't talk about it, who is to know? Last year's annual Ynet-Gesher opinion poll in Israel showed that fully 35% of Israeli Jews don't observe the Yom Kippur fast. The most fast-observant were the most Orthodox-leaning respondents. The least fast-observant were the secular Israeli Jews. I leave it to readers to decide who in that poll American Jews most resemble, but after reading the results I have no doubt many a cup of coffee will be drunk before the people with whom I will share YK day make it to the sanctuary on Saturday. So as far as I'm concerned, I'm in good stead.

The real question is what are we supposed to be achieving on Yom Kippur? Vayikra (Leviticus) 16:29 tells us literally "t'anu et-nafshoteichem"--afflict your souls--on this day. Isaiah tell us in ancient times those words were an idiom for fasting. In fact, the famous Haftarah reading from Isaiah (58:14) on Yom Kippur morning cautions us not to turn the fast into a fetish. The following is excerpted from a wonderful 2010 translation by "Velveteen" Rabbi Rachel Barenblat:

"No!

This is the fast I want:

unlock the chains of wickedness,

untie the knots of servitude.

Let the oppressed go free,

their bonds broken.

Share your bread with the hungry,

and welcome the homeless into your home.

When you see the naked, clothe them.

All people are your kin:

do not ignore them.

"Then you will shine like the dawn,

and healing will rise up within you.

Your righteousness will vindicate you;

the presence of God will guard your safety.

Then, when you call, Adonai will answer.

When you cry out

God will say, 'Here I am.'"

I do believe that many, many Jews find incredible spiritual, emotional, and repentant meaning in the tzom. Many, if not most connect with one, or some, or all of the reasons for fasting that our tradition--and our families--have set before us. But I don't connect with fasting aimed at spiritual ends, and those reasons don't have meaning for me. I know it's doubtful I'm the only one to feel that way--even among observant Reform Jews. And I feel that blindly going along anyway when the result is not the one intended gets one dangerously close to fetishizing. The fast was never intended to be an end in itself.

What to do when that's all you're left with?

In our tradition, first we do and then we hear. First we perform the commandments, and then we perceive their value--in holiness, in ethical behavior, in chesed (loving-kindness), or often simply in deepening of our connection with God and others in spite of the seeming irrationality of certain rituals. But what happens when we do and then we don't hear? Such is the exact essence of my question.

Maybe Rabbi Schaalman had a point. I, for one, don't need a special day set aside to afflict my soul. I am perfectly, pessimistically, masochistically, fatalistically, bleeding-heartedly, guiltily, pathetically, yearningly, sobbingly, choose-death-or-live-righteously, Adonai please let me just lay my head in your lap-ingly able to go there inside of myself at the drop of a hat, at a moment's notice, at any time of day or night, 24/7/365. For all the crustiness on the outside (as my blog and Facebook feeds might sometimes suggest), the untold story is almost always haunting myself, bowing before the Eternal, and seeking amends with my friends and family very closely after my occasional ass-hattishness.

Maybe it's derived from my years in 12-step. Maybe it's just how God made me. But when you get right down to it, I am a deeply emotional, deeply affected by others, human lump of pathos who cracks in half in heartbreak at my own behavior and my effect on others. All. The. Time. Others may not know I go there all the time.

But God does.

The only time I don't go there is during the Yom Kippur fast. I honor others who are able to find their way inside of themselves, to pray for repentance via the tzom. The only place I find myself, however, is trapped inside a headache, craving water, and praying for fried chicken. And no amount of telling me that that's the "wrong" way to be affected by the fast is going to change that. For me the fast actually places my focus directly on myself and my physical needs, so that the crying out of my body crowds out any thought of others or my relationship with them. My effect on others at all? Much less others going hungry on the planet? You have got to be kidding me.

That doesn't make me an unobservant Jew, much less a bad one. It most likely makes me like many of the other people with whom I will share Yom Kippur services this year. And if the places I am barred from inside of myself by the fast are the ones to which I'm intended to go--what is the point of observing the fast in the first place?

I know, I know. Many Jews reading this post have this voice screaming in their heads right now, "Because...! Because...!" So I ask you to tell me in the comment thread below your honest answer. Because...why? Because the mental, emotional, and spiritual gymnastics required for me to find a satisfying, fulfilling, workable answer to that question that would fill in the missing link between fasting and repentance and still be in keeping with the denominational principles of Reform Judaism have wholly eluded me for three years.

Either I make of myself (what by my own personal estimation feels like) a hypocritical Reform Jew by fasting, or I make of myself a hypocritical faster by ignoring (what is my own personal understanding of) my denominational principles and lack of an inner connection in doing so.

Or, of course, I don't fast. And in not doing so, maintain my connection with the force I cannot name that draws me inexorably closer and closer every day. There are derechs and there are derechs. Some are mainstream. Some are not. We all hope ours points in a holy direction. I don't need to read the inscription to know that this is mine. As for where it may lead...that's something I'm waiting to hear.

May you have an easy fast. Or no fast at all. But whichever you choose, do let yourself go there. Down into that place where you are real about who and what you are, what you have done, and what you wish you did differently, nakedly and humbly before your God. Because that is the real point.

And may you be well inscribed for a wonderful, prosperous year in the Book of Life.