String Theory

Honest Reform Jews struggle to determine whether they feel commanded to respond to individual mitzvot. Sometimes they arrive at controversial conclusions. That's how I started wearing tzitzit.

Yep, that's me wearing tzitzit. Last thing first, I'll get to how I got to tzitzit in a minute. More germane to the Reform circles in which I run--tzitzit are controversial. There are some rituals Reform Jews rarely adopt, no matter how deeply they've searched their souls to determine whether individual mitzvot (commandments) have meaning for them.

But even though modern Reform has come a long way from its classically inspired tendency to reject most traditional ritual practices--from a distance, these days it can be hard to tell a Reform shul from a Conservative one--there are some things Reform Jews "just don't do." Although our movement demands us to be thoughtful and open-minded about the mitzvot, deeply ingrained knee-jerk reactions to ritual practices that resemble stuffy, old, or (horrors!) Orthodox Jewish practices still exist. Very often, wearing tzitzit is considered on the other side of some allegedly uncrossable line between Reform and Orthodoxy.

I'm no great fan of Orthodox religious haughtiness [Ed. note--though I'm coming to think such haughtiness is evenly balanced by the unfortunate tendency of Reform Jews to misrepresent our own movement--see quote below] , but I am a Jew in awe of our multiple millennia of tradition. And as a convert (as any Jew-by-birth will tell you), I tend to take that tradition a.) pretty seriously, and b.) without a lifetime of inter-denominational baggage to weigh me down. So I don't categorically exclude commandments just because other denominations of Judaism tend to include them a lot more than does my denomination.

Denominationalism, itself, deserves a note here. I am a member of a Reform synagogue community. I pay dues; I sit on committees; I attend worship services. I read a lot about Reform Judaism during my conversion studies, and happen to agree with the movement's stance on halacha (Jewish law)--that individual Jews have a right and a duty to determine how to intersect with the mitzvot themselves.

However, I also researched all streams of Judaism and rituals and styles of observance both near to and far from normative Reform. In fact, I consider myself a Jew first and foremost--a Jew who happens to agree with the Reform perspective, and who believes it's my responsibility to financially support my worship community of choice. But I think the breadth and beauty of Jewish tradition is too amazing to for anyone to let others define their Judaism for them, to choose to squeeze their Judaism into a neat and tidy denominational box. If I didn't maintain a synagogue membership (with

RippityRyan), I guess that would make me a "post-denominational Jew." Except I do think that denominations and synagogue communities matter--quite a lot. Just not enough to serve as an intermediary between Adonai and me.

So...what are tzitzit anyway? The Torah (Hebrew Bible) commands Jews to tie tzitzit (stringed fringes) to their four-cornered garments as a way to remind us of all the other commandments--so we'll remember to (drum roll) follow them. Four-cornered garments aren't common anymore, so many traditional Jews were a special garment called a tallit katan (small prayer shawl) in order to have somewhere to affix tzitzit.

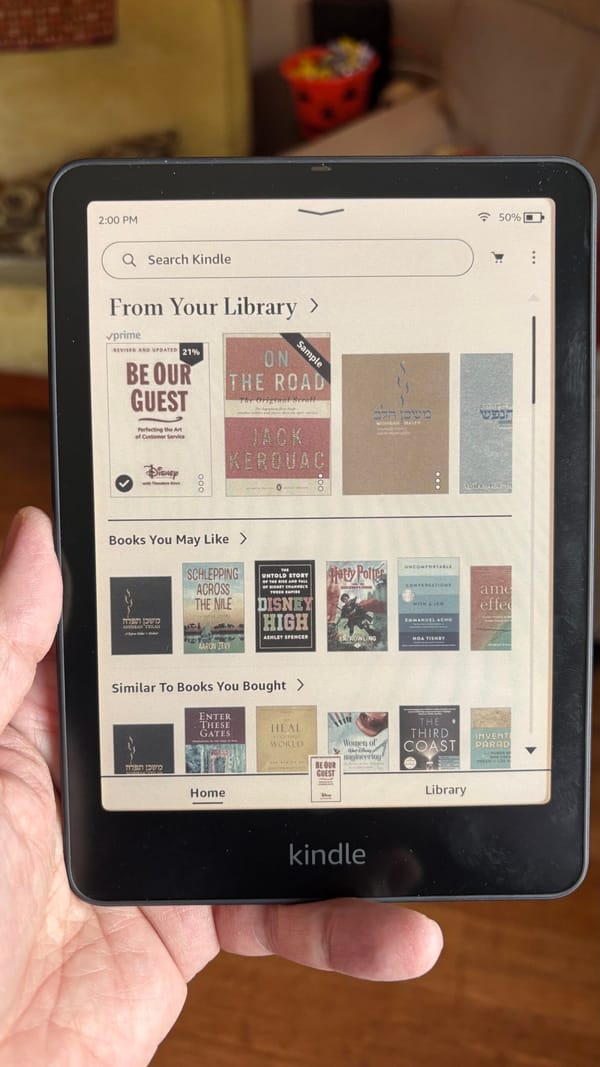

There are many interpretations of how to do all this, with styles, sizes, materials, methods for tying the tzitzit, whether they should include a special blue thread, and whether to wear the tzitzit--and even the tallit katan--under your clothes our atop them all differing depending on whom you ask. None of this is germane here (though watch this terrific Punk Torah video for a short and groovy discussion of all this.) The bottom line is after a lot of forethought, the mitzvah definitely spoke to me.

In fact, the commandment concerning tzitzit is quoted in the V'ahavta, sort of the central statement of Judaism commanding Jews to always keep God's mitzvot top of mind (immediately following the Sh'ma, Judaism's central declaration about the oneness of God.) Reform siddurim (prayerbooks) removed the paragraph concerning tzitzit for many decades. It returned in the most recent Reform siddur, Mishkan T'filah, but only as an option, and only if you choose to turn the page to find it.

Well I turned the page and found it, and thought about it. I looked for examples of Reform Jews who chose to wear tzitzit. The best example by far (though mind you, there are very few examples) was David A.M. Wilensky, the noted, 20-something, east-coast Reform blogger and writer. He wore tzitzit--though no kippah (as he notes, kippot are merely a tradition but tzitzit are a commandment)--for several years before ceasing the practice in 2010. He did so because he felt commanded to do so, and he received a fair amount of criticism for it, too.

Similarly, David and I both have a love-hate relationship with the Reform powers-that-be, and an unquenchable thirst for Jewish knowledge and exploration. But it takes guts to wear tzitzit in a Reform community. David had them. I decided to find out if I did, too.

I've spoken to many Reform Jews who casually dismiss mitzvot they find onerous, outdated, or "Orthodox" by saying one version or another of the following sentence:

"We don't have to do that. We're Reform. We can do whatever we want."

Problem is, that's not true. Reform Judaism allows individual Jews to make decisions regarding following the mitzvot for themselves, unlike other denominations which consider all mitzvot binding and only allow denominational or other rabbinic authorities to decide whether and where any wiggle room might exist. But Reform Judaism never tells Reform Jews to discard the mitzot out of hand. What Reform Judaism really asks is for Reform Jews to examine the mitzvot and determine how they speak to us, what meaning they hold, how deeply they move us, in order to decide which ones we want to--or for some us us, which ones we must--accept and adopt.

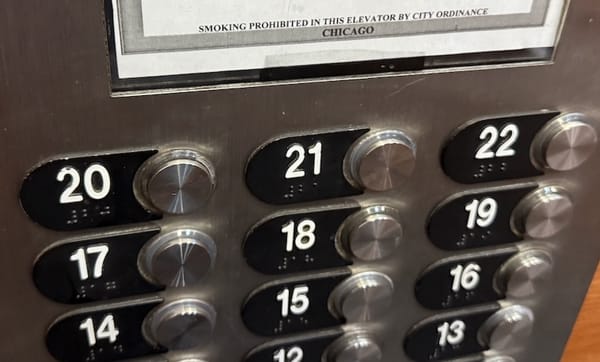

I turned tzitzit over and over and found in my heart a sense of being commanded to respond to the commandment to don them. That's the best I can explain it, though I think that's a pretty good explanation. So after much coaxing, Rippity and I made a special trip to

Snootier-Than-Thou-Orthodox-Judaica-StoreRosenblum's in Skokie and I bought a tallit katan. Two, even.

I wore them at work last week, to synagogue Friday night, and to a synagogue karaoke event on Saturday. They were an amazing topic of honest and interested conversation at work, which touched me. They earned a couple of sideways stink glances at synagogue on Friday night. By Saturday night, no one cared (or was too tipsy to notice.)

How I care is another story. I'm not sure if this is a long-term thing or a passing exploration, which is a valid place to be with a new mitzvah. Tzitzit could go the way of my former dietary restrictions, or it could stick around like my beloved tefillin practice. Only time, my heart, and Adonai will tell. At any rate, my cantor was kind enough to record the V'ahavta paragraph concerning tzitzit in trope (cantillation melody) for me so I could add the paragraph to my personal morning prayers.

One thing I can say already is be careful how you wash your tzitzit if you go cheap like I did. Discount Neatzit are no match for delicates laundry mesh bags. It's just as well. One thing I did learn before I double-wrapped my unraveled tzitzit and placed them in the trash (yes, just like double-wrapping taken challah before tossing it) was that stringy strings don't cut it for me. I definitely want to explore a more traditional tallit katan and more robust strings. Which may be a clue about where my heart is concerning tzitzit after all.

That doesn't make me Orthodox--and Orthodox isn't a dirty word, either. It makes me a thoughtful Reform Jew engaging with the tradition that belongs to us all. That doesn't mean I won't continue to get the stink-eye from some people if I choose to continue to wear tzitzit (hanging out, thank you very much.) If anything, I think what it does mean is that Reform Jews have a right to explore all Jewish tradition--and a duty to follow their hearts where that tradition leads.

If you're a traditionally minded fellow Reform Jew reading this, Jewish tradition is your tradition. All of it. Let your love for it guide you. May the example of your thoughtful intersection with our tradition be the best answer--and an inspiration--for Reform Jews everywhere who may be silently yearning to explore beyond the confines of what some uninspired folks may suggest is normative Reform Judaism.

A great place to start is, simply, turning the page.