Shake Hands with Whose Uncle Max?

All Jewish converts face the challenge of fitting into Judaism and into a Jewish community. But how do you find your comfort zone in a sanctuary echoing with the sounds of chanted Hebrew, and full of people with last names and lifetime experiences different than yours? You do, with practice. And tim

I love davenning shacharit (saying morning prayers), but as with all things formerly unfamiliar there's one thing I never counted on. Tefillin hair. When I began laying the ritual leather phylacteries on my arm and forehead, it took awhile to realize that the hair bump in front of my kippah was from my shel rosh. That's something I might have learned if I had grown up Jewish. (Even if I had grown up Reform, I'm sure I would have had an Orthodox grandfather or uncle somewhere to learn this from.)

The stress of being the new Jew in a room full of lifelong Jews. It's something all Jewish converts face--especially during the conversion process--but that feels unkosher to talk about with fellow congregants. Yet, it's valid to feel out of place when for the first (or even the second, third, or fourth) time in your life, you're the sole Foley in a room full of

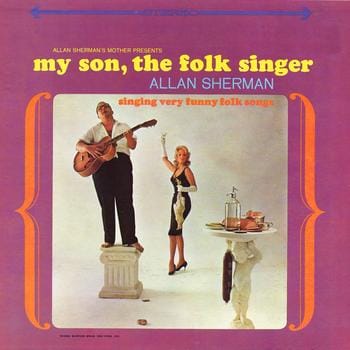

"Smallowitz, Wallowitz, Tidelbaum, Mandelbaum, Levin, Levinsky, Levine and Levi, Brumburger, Schlumburger, Minkus and Pinkus, and Stein with an 'e-i' and Styne with a 'y'."

I was an Allan Sherman fan when I was eight, so that lyric from Shake Hands with Your Uncle Max has been in my head my whole life. In fact, growing in New York City, I've known families with last names like that my whole life. But even with most of my lifetime's closest friends having been Jewish, I still found it a shock early in my conversion journey the first time I realized I was a non-Jew standing in a synagogue full of lifelong Jews.

My first time at synagogue (nearly a year ago, now), if I hadn't already been punishingly aware that I didn't share the same background as the people surrounding me in the pews when the chanting and bowing started, my inability to follow along or figure out the choreography made it obvious to all. I can remember fearing that Jews sitting near me would judge me for my lack of knowledge, and for my newbieness. When the service was over, the man who is now my rabbi came over and asked, "So, have we totally alienated you yet?"

"No," was my answer. "No, but..." was my unspoken thought. But what was that bowing about? But how will I ever learn all of this? But does everybody here speak Hebrew? But what was that camp thing where the people sitting behind me were talking about sending their kids next summer?

But all of these people share common backgrounds and experiences directly related to their Judaism, and I wish more than anything in the big, fat, whole, wide world that I did, too, because I am so in love with Judaism. But how can I ever make up for that and stop feeling like such an outsider?

I remember how pungent this anxiety was for me. I've had concerns like this shared with me by my partner, Ryan, who is undertaking conversion studies. I've read about such angst on the blogs of my fellow Jews-by-Choice. One blogger in particular, the fabulous Erika Davis of Black, Gay and Jewish who officially became a Jew only yesterday, still openly struggles with how to conceive of her identity as a black woman and a Jew at the same time. Even though Jews come in every color of the spectrum, that kind of inner struggle is absolutely valid.

I think the answer to all of the "buts" that we new Jews and soon-to-be-new Jews share is, simply, time. It takes time to get used to any new situation, and frankly, being the new Jew (or new pick any religion) is one heck of a new situation for anyone to cope with. But the commonalities we share with our native Jewish brethren outweigh the differences. Those commonalities are love and compassion, a desire for justice and fairness, a yearning for peace. All things, I might add, tied in with the mitzvot (commandments) that undergird the Jewish faith.

As a conversion candidate, you may find it hard to pronounce the last name of the person sitting next to you in shul. They may look different than you do, and have knowledge about different topics than you do. But how would that be any different than the things you might be able to say about the person sitting next to you on the bus, or in a restaurant, or in your row of cubicles?

No, new Jews cannot go back in time and attend summer camp, study for young-adult b'nei mitzvah ceremonies, or invent Jewish Bubies and Zadies (grandmas and grandpas.) Then again, fellow congregants can't go back in time and relive your life experiences, either. And they matter just as much--add just as much meaning and context--to the ancient and continuing story of Judaism as do the Jewish experiences of lifelong Jews.

Figuring out the Hebrew prayers, the nusach (melodies), the choreography of the worship service, the meaning of commonly spoken Yiddish phrases, and the alphabet soup of acronyms that describe Jewish community institutions, all of that comes with study. If you're a conversion candidate, you are already studying, just give it time. If, like me, you've already converted, you probably realize you'll be continuing that study very happily--if not voraciously--for the rest of your life.

Feeling comfortable with the cultural differences just takes time, too. I can't give you a timeline, but look at it this way. Who would you want to sit next to every Friday night at shul: someone who doesn't share your last name; or someone who doesn't share your ethical worldview? It's that ethical worldview that matters--it and a shared sense of the nature of God are what draw conversion candidates to Judaism in the first place. And a year or two from now, it won't be the surprise of the differences between you and a lifelong Jew that will make you stop and wonder.

It will be the surprise of remembering that once you weren't a Jew.