First You Do (the High Holy Days), and Then You Hear

The High Holy Days that marked the beginning of 5772 also marked the end of my first observed Jewish year. I expected the Days of Awe to be fulfilling. But what was missing turned out to be the best part of all.

I remember how helpless it felt last year (in 2010 or 5771, take your pick), to be on the verge of a Jewish journey only to have to stand on the outside looking in for a few weeks while the Jews I wanted to join observed the High Holy Days. I wouldn't have understood much about them had I experienced them then. But during my conversion journey and subsequent first few months as an official Member of the Tribe, they loomed ahead like an angst-inducing capstone experience to mark the end of my first year living Jewishly.

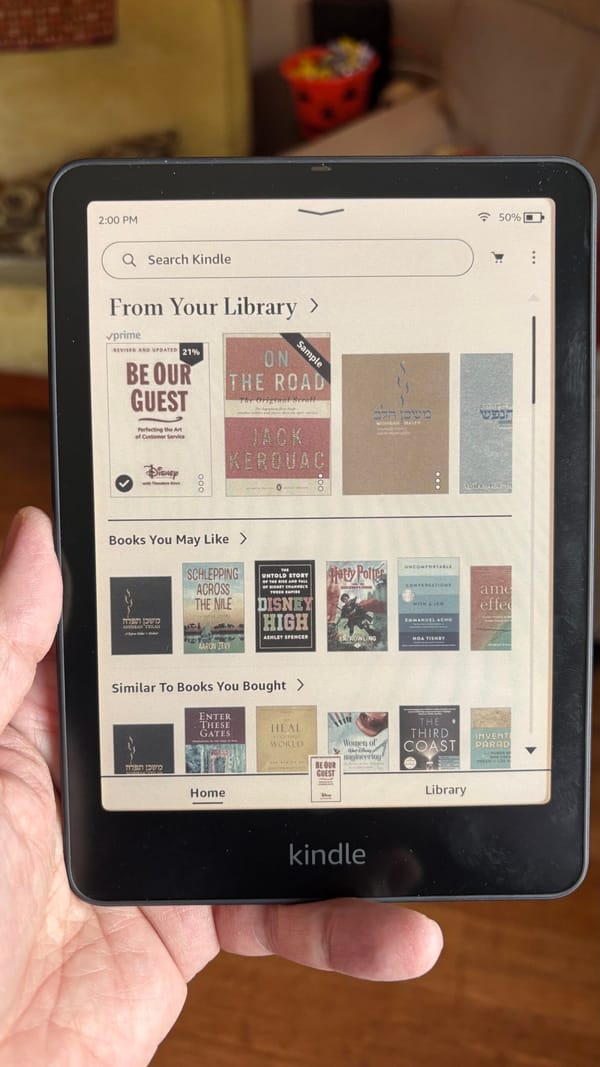

I was surprised at how edgy I felt as they got closer. I feared the Reform movement's old machzor (High Holy Day prayerbook), which isn't fully transliterated like the movement's regular prayerbook (Mishkan T'filah.) I feared being bored or overwhelmed by hours and hours spent in synagogue. And I wasn't sure whether I could find within me the willingness or, frankly, a reason that made sense to fast for 25 hours on Yom Kippur, Judaism's holiest day of all.

In the end, the machzor was nothing to fear. After a year of synagogue attendance (and almost a year for Ryan), we both were able easily to figure out a lot of the hundreds of pages of service. (Hurray for the Jewish worship service being so conveniently consistent.) And what we couldn't figure out, most other people couldn't either (digressionally, a lack of adult Hebrew skills that serves as part of the reason some traditional Jews don't think liberal Jews know enough about Judaism)--so many Hebrew passages were skipped in favor of English paraphrases elsewhere on the page.

The time commitment turned out not to be scary, either. Truthfully, at this point I seek out reasons to be at synagogue, whether for worship, learning, or community events. So although Ryan and I both did get a taste of "High Holy Day overload" during the Days of Awe, it wasn't exactly an overwhelming experience, either. For unfamiliar readers, the Jewish calendar is full of festivals large and small, and the Jewish High Holy Days begin what amounts to a month of them. The core days are the ten "Days of Awe" from Rosh Hashanah, when the Hebrew calendar year goes up one, to Yom Kippur, the well-known "Day of Atonement."

Tradition holds that during these ten days, God has the Book of Life for the coming year open, and Jews must take the opportunity to ask forgiveness and atone for sins committed against God and other human beings before God closes the book at the end of Yom Kippur, inscribing the names of those who will live through the coming year--and those who will not. It's notable that in Jewish tradition, God's forgiveness is always available--but the forgiveness of fellow human beings is not. So the gist of the High Holy Days is an annual opportunity to reconsider hardened positions, reconnect, and make peace with the people in your life. Frankly, I found ten days of that message to be breathtaking. Even if it meant multi-hour synagogue services on Slichot (a late Saturday evening service before Rosh Hashana), Rosh Hashanah eve, Rosh Hashanah day, Kol Nidre (the high-stakes Yom Kippur eve), and--your Jewish friends do not kid you--all day on Yom Kippur from morning until sunset.

Those 25 foodless hours, though...in advance of the High Holy Days, I understood the point of not eating--and, importantly, not drinking, either--during Yom Kippur to be a way to help one focus on atonement and things of spiritual importance. At least, that's partly how the Jewish sages interpreted the Torah's command to "afflict your souls" on Yom Kippur. Trouble is, I didn't get it. That surprised me, because Jewish ritual is very important to my daily life as a Jewish man and carries an enormous amount of meaning for me. But starving myself has never been on the table for me, so to speak, in order to achieve religious ends.

Much like I did during Passover, I hemmed and hawed, and for a couple of weeks expected that I wouldn't fast at all. After all, as a conscientious Reform Jew, if you can't find a way to connect with a mitzvah (commandment), there isn't much point in doing it. I had no doubt Ryan would fast--his Jewish journey has in some ways turned out to be even more observant than mine. But until the last moment, I was dead set against it.

However, as the Torah notes, ours is a tradition where first we do and then we hear. In other words, conscientions Jews don't knock it until they've tried it. So after a fortifying dinner the evening of Kol Nidre, we lit our Yom Tov candles, said goodbye to food and drink, and went to services. By midnight I knew I was going to fall off the wagon, and went into the kitchen to stave off a headache with a glass of water and some Annie's cheddar bunnies. They didn't help much. I awoke with a raging migraine, tried to stave it off with a glass of orange juice (lifelong Jews know what I am about to write), and ended up on my knees wretching into the toilet.

So back to bed as Ryan left without me for morning services on Yom Kippur, a day I'd waited for all year. But I was one of several community members making comments at the afternoon service, so I knew I had to get myself together somehow. After all, I hadn't written a word of what I was going to say, and needed to find a way to scrape myself out of bed and put two words together about "What Judaism Means to Me"--and of course, ignore my physical misery enough to actually make it to synagogue.

In the end, I made it out of bed, wrote those two words, made it to synagogue, and made it through the rest of Yom Kippur back on my fast. After all my hemming and hawing, I did find meaning in the fast, too--as much of it as I managed, anyway. I can't tell you why; I didn't expect it to work that way. But somehow, in the doing, I managed to get the point after all.

It's a lesson I applied to my comments. All along, I knew I wanted to speak to the people in the last row, the ones who only ever come twice a year (Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, just like twice-a-year Christians whom you only see in church on Christmas and Easter.) But until Yom Kippur morning, I couldn't figure out what to say to them. Then somehow, the words all just came. Here's what I shared standing before my congregation on Judaism's holiest day, one Hebrew year after being an outsider on the same day:

I remember many times spent in the last row of holy places during the major holidays of my birth tradition, wondering what I was doing there. I recall wishing I had the same sense of connection as other people in those places with me, and wondering where I would ever fit in.

My Jewish journey made it pretty obvious the biggest reason why I didn't fit in. I believe I've always been Jewish, and it has been my life's journey to figure out my soul's native vocabulary. After this past year of that journey, I'm aware that the gnawing sense of emptiness that I used to carry around with me every day is no longer there.

I'd love to tell you it's because of the High Holy Days, but I'd be lying. Instead, I know it's because of a year spent not only living Jewishly, but participating in the community life of Emanuel [Congregation--my synagogue.] Looking out at this sanctuary, I can see the faces of many new and dear friends who have supported my journey, next to whom I have sat through a year of worship services, Share Shabbat family dinners, and roundtable discussions, with whom I sang around the campfire at OSRUI [a Reform Jewish overnight camp in Wisconsin] over Memorial Day weekend. The sense of love and support among members of the Emanuel community is remarkable. There is something very special here, and I am grateful to be a part of it.

I know that some of you out there are probably like me. Back there in the last row, unfamiliar faces, you may be here just for Yom Kippur, and feeling the same kind of emptiness I carried around for so long. I wish I could tell you that beginning to participate in the community life of this congregation would help heal that emptiness, but I can't. Everyone's experience is different.

But ours is a tradition where first we do, and then we hear. So I wouldn't be surprised if you found that engaging a little bit more in the life of this synagogue brought you a similar sense of belonging. In the year ahead, I hope to get to know some of you--to have the opportunity to sit next to you in this sanctuary every once in a while on a day that isn't a High Holy Day, to participate with you on a committee, to eat with you at a Share Shabbat.

Most of all, I'm grateful that you're here. Because of the many places you might choose to spend your time, this is a place where you are home. You are welcome here. You are wanted here. And this is a place where you belong.

Chatimah Tovah.