"Do you feel any different?": My Mikveh Day Report

My mikveh day was amazing and surprising in ways I'll never forget. It changed me forever--but it took me all day to figure out just how. Here is my epic look at the day I officially joined the Jewish people.

So Thursday I became a Jew. The capstone rituals to my months-long conversion journey took about an hour. I described what those "mikveh day" rituals would be in detail a few weeks ago (see How We Make a Jew.) But even after running mikveh day through my head for weeks in anticipation, the actual experience was still an amazing, humbling, unexpected shock.

I also tried to find detailed first-person blog posts about mikveh day during my conversion studies to help give me an idea of what to expect, but there aren't many out there. (Two really great Reform-inspired accounts I did find are here and here.) So I'm adding to the record with my own. Here's what happened on the day that I became officially Jewish--in long-form, epic-post format. For detailed descriptions of the process and rituals I talk about below, as well as links to authoritative Jewish websites on the topic, browse through my How We Make a Jew post, linked above.

"Today's the last day I'll wake up as a gentile." After weeks of day-dreaming and an almost sleepless night of anticipation, at 6:30 a.m. on Thursday (May 12, 2011), I decided caffeine was the only breakfast my nerves would let me ingest. I left Ryan in bed, got dressed at warp speed, then spent the next 90 minutes trying (and failing) to down a single cup of coffee. When he finally awoke, Ryan tried to make conversation with me, but all I was able to get out was one or another version of, "Oh, my God, today's the last day I'll wake up as a gentile--I'm never going to wake up again as a non-Jew." It hit me hard that from the moment I got up that day, the rest of the day--and of my life--would be Judaism-related. Being a ger, a stranger, had already come to an end--and I had slept through it.

I put on easy-off clothing--jeans, a short-sleeved shirt, and sneakers--donned the blue-and-white crocheted kippah with a Magen David on it that fellow blogger Chaviva Galatz got for me in Israel, Facebooked and tweeted that my mikveh trip was underway, and headed for the car with Ryan. We had already made two dry runs to the Reform-friendly Community Mikvah of the Conservative Movement at Beth Hillel Congregation Bnai Emunah in north-suburban Wilmette to make sure we knew how to get there.

The 17-mile rush-hour trip up the Kennedy and Edens expressways from the Loop took 45 minutes. We had just enough extra time for me to not drink a second cup of coffee from a service station convenience store near Old Orchard. While Ryan went inside to get the coffee, I sat in the car and tried not to cry. Then I checked Facebook, saw a stream of warm welcomes and "Mazel Tovs!" from synagogue and secular friends, and began to lose it. I figured that tearing up in a parking lot was better than tearing up in front of my beit din.

"Nobody likes a show-off..." Most of my beit din was already at the synagogue when we arrived--our rabbi and cantor, Rabbi Michael Zedek and Cantor Shelly Drucker Friedman, from our home synagogue, Emanuel Congregation. ("Our" because Ryan is a member along with me, as a family unit.) Also there was our good friend David, a longtime temple Brotherhood officer whom I had invited for already-Jewish moral support.

While we waited for the third member of the beit din (and much to my anxiety, my mohel) to arrive--Cantor Larry Elsberg--Rabbi Zedek got a head start in filling out my conversion certificate. "What's the Hebrew date today?" he asked Cantor Friedman. Before she could answer, I whipped out my Android phone and displayed my Hebrew calendar widget. "The eighth of Iyyar," I answered.

"Oh, look at you," Cantor Friedman joked. "Well, nobody likes a show off. But listen, there's something I ask everyone. I'm always curious to know, does it feel any different the moment after mikveh." I told her I bet it would. Little did I know I'd have two more answers for her before day's end.

"Why don't you tell us how you got to this moment." Shortly after, Cantor Elsberg showed up and my now-completed beit din bid a temporary goodbye to Ryan and David and led me to a private meeting room. With my fate as a future Jew now in the hands of these three people, I took the sun streaming through the room's skylight as a good sign. Not to mention the ironic small puddle of water accidentally pooled in the middle of the big, wooden table by the cleaning staff. I sat on one side, the members of my beit din on the other, and the conversation began to determine my readiness to join the Jewish people.

No one's rabbi convenes their beit din without knowing that they're already ready, but I didn't expect the following moments. "Don't be nervous, this isn't a test," Rabbi Zedek said--or as Cantor Friedman had told me a few weeks earlier after noting how Jewish I seemed to be already, "it's a mere formality." He asked her if she wanted to start. She just smiled at me and said she had no questions.

So Rabbi Zedek asked me to tell the story of how I had gotten to this point. I told them that I never inherited my family's Christianity, how as a small child I never accepted church doctrine. I told them about growing up with substance-abusive siblings, and how that led me to an emotional recovery program as an adult. I told them about spending most of my adult life with a private sense of God, and eventually finding spiritual shelter in Buddhism.

I also told them about the day last year when, thanks to my recovery program, my sense of God became so strong, the bottom fell out. Buddhism gave me no avenue to have a relationship with God. I couldn't share my 12-step fellowship with members outside of the rooms. I couldn't go back to a faith I never accepted in the first place. I told them about the afternoon I felt so spiritually homeless that I sat on my couch and sobbed for an hour.

Then I told them about the ride on the Brown Line. That same week, I asked God to guide me, finally, to where I belonged, then got on the Brown Line with my laptop to blog from a Lincoln Square cafe. On the way, and by way of a last-ditch effort, I searched Wikipedia for world religions. I spent most of the thirty-minute ride reading about Judaism. And in the end, I did break down in front of my beit din when I tried to describe the sense of walking down the stairs from the Western Brown Line station knowing that half an hour after asking for guidance, I knew I had found my home. As I wrote in my conversion essay, Judaism describes the innermost parts of me so exactly that this has been a journey without a doubt.

Once I pulled myself together, Cantor Elsberg asked me about aspects of Jewish life that I found meaningful. (Shabbat observance, the continuous ritual of brachot--or food blessings, Jewish holidays.) Rabbi Zedek asked me why join a people so many other people hate. (Because the same people who want to kill me for being gay would want to kill me for being Jewish, so it's a wash.)

Then Rabbi Zedek threw me a curve ball. He said I was already one of the most faithful participants in synagogue life and asked me how I make that jibe with knowing that many other members--and many other Reform Jews--rarely participate in the life of their religious community at all. I learned the answer during my conversion journey from personal experience--there is a prophetic aspect to being a Jewish convert. We converts are hard-wired to take Judaism with joy and sincerity and totally in earnest because it's so new to us, and because of that we often serve as an inspiration to born Jews who may have lost their sense of wonder about their native religious tradition. Maybe that's the point. Maybe it's supposed to be that way.

Finally, Rabbi Zedek asked the six ritual questions all conversion candidates must answer. Essentially, of your own free will are you joining the Jewish people, giving up all other religions, and willing to defend Judaism and the Jewish people, live Jewishly, keep a Jewish home, and raise your children as Jews? Absolutely.

"Thank you, Michael, would you please wait outside?"

"You take a deep breath, then a quick leap." Two minutes after I rejoined Ryan and David, the beit din emerged and congratulated me, at which point I was sure everyone could see the cartoon thought bubble hovering above my head, "Oh, my God, this is it. I'm about to become a Jew." We retrieved Carol, the mikveh attendant, and headed outside to come back in through the separate mikveh door. It was a smaller facility than I expected, essentially a loop of rooms beginning with a long, narrow waiting room leading to a preparation room with two lockable doors, one of which led on into the mikveh room, which paralleled the waiting room on the other side of a shared wall.

We all squeezed into the waiting room, then Carol explained that anyone Jewish is welcome to use the mikveh to mark a religious or special occasion, but that conversion is the only use of a mikveh governed by Jewish law. Then she laid out what was about to happen: I would enter the preparation room with Cantor Elsberg where he would perform hatafat dam brit, or a ritual circumcision (i.e. the ritual for when someone is already circumcised.) Then I would remove everything from my person, brush my teeth, floss, and shower to ensure nothing would come between me and the mikveh waters, and signal my readiness to enter the water.

Privately Carol showed me how to immerse. "We're too buoyant to immerse on our own. So you hold your hands in front of you pointing down, you take a deep breath, then a quick leap up. The force of coming down immerses you under the water. Then lift your legs up so that you don't touch the bottom to ensure that for an instant, you're floating free." This was instantly more work than I thought it would be.

"Pull down your pants and pull up your shirt." A couple of minutes later, I was back in the preparation room with Cantor Elsberg while he explained what he was going to do. I am absolutely certain some readers (ahem, male ones) will arrive at this post solely for this section. Cantor Elsberg assured me hatafat dam brit would be painless. I had my doubts.

He told me he would sit (in this cramped prep room, on the closed toilet!) and I would stand in front of him with my pants down and my shirt pulled up. Then with what eventually turned out to be a teeny, tiny lancet, he would draw a drop of blood from along the side of you-know-where, collect it with a cotton swab, and show it to the rest of the beit din for them to witness evidence of my entrance into the covenant of Abraham.

"You'll feel a little cold at first, because I have to apply alcohol to make the site sterile," he said, getting down to business. "The only thing to remember is don't move around. Are you ready? That's it. I'm done."

Clap your hands. The length of the sound your hands just made is about how long the lancing took. It felt like a slight scratching for a split-second, wasn't painful at all, and in fact was so innocuous, all the worrying I had done in advance of the procedure left me feeling ridiculous. As did the fact that my penis sat for the next two minutes in someone else's hand.

"Breathe, don't stop breathing. We have to get blood to the site, so just keep breathing." Why? Is it on life-support?

"You're doing fine. There was only one person who almost passed out on me, and he had just had coffee for breakfast." Are. You. Kidding?

"We're almost there." Really? Because I could stand here for another couple of-

"There, all done! See?" I didn't, the drop was that small, as I had been warned it would be. It made no sense to raise my pants as Cantor Elsberg left the room with the evidence, but I did, only to drop them again and start my final preparations. I didn't think I took very long, either, until I heard Rabbi Zedek call from behind the door, "Michael, cleanliness is next to Godliness, but come on!"

"Okay, Michael, whenever you're ready." I signaled my readiness, entered the mikvah room alone, hung up my towel, and stood, naked, in front of the mikveh pool. It was deeper than I had anticipated. I held the railing and stepped down the seven steps--each one representing a day in the Creation story, into the most buoyant pool of water I've ever experienced. The warmth of the water--approximately body temperature--and, I suppose, the chemicals necessary to keep it clean use after use gave it the feeling of olive oil (the way many people describe the feel of the Dead Sea.) It made it impossible to move quickly, and hard to keep my feet on the bottom. I was also surprised to find the water coming up to just below my shoulders.

Everyone but Rabbi Zedek would only hear what came next from behind a privacy screen between the waiting room and the mikveh pool. Rabbi Zedek would be my shamas, or witness, to ensure my immersion was kosher, or halachically (legally) acceptable. I thought I would cry my way through the three immersions in the mikveh that would make me Jewish. As it turned out, I found myself concentrating so hard on doing it right and not forgetting anything that the experience was mostly keva (prescribed prayer and ritual) instead of kavanah (heartfelt intention.)

But keva is enough to get the job done. I took a deep breath, took the biggest leap of faith of my life, and jumped up and down into the water. It was easier to do than I thought. As I tucked my legs up I could hear Rabbi Zedek call out, "Kasher!" from under the water. I came up, put on the kippah at the side of the pool, and said the blessing for immersion.

Then I leapt up and in a second time, and again heard, "Kasher!" from underwater. I came up and said a silent prayer. I asked God to make me a good Jew. I asked God for Hebrew skills. Then in Hebrew I recited the Shema, Judaism's central statement ("Hear, o Israel, the Lord is our God, the Lord is One"), holding the final word, Echad ("One"), for as long as I could.

And then it was time. The third immersion, after which, the moment I emerged from the water, I would be a Jew. For a few seconds, I thought I would cry, but the struggle to stay on my feet brought me back to my senses, as did Rabbi Zedek. "Okay, Michael," he said, "whenever you're ready."

"Rabbi Zedek," I said, "I've been ready for forty years." And then I dunked, heard "Kasher!", came up and was Jewish. But before I could celebrate, there was the final blessing to get through. It was like the moment at the end of Star Trek: Voyager when they finally made it home to the Alpha Quadrant but still had to shoot their way out of a Borg Cube, first. Wade over to kippah. Put on kippah. Say the Shehecheyanu.

And then it was over. I was a Jew. There was a group "Mazel tov!" as Rabbi Zedek left the mikveh room, followed by Cantor Friedman leading a rousing round of "Siman Tov", the familiar good-luck song from Jewish weddings. As I stepped up out of the mikveh, I should have felt elated. But in an effort to make sure my third immersion would be kosher, I had leapt a little too high with my left arm a little too crooked and ended up pulling my back as I went down. The only thing I thought as I emerged from the mikveh and for several minutes after was, "Ouch!"

On the other hand, I pulled my back in the mikveh?! Oy, how Jewish am I?

"Do you feel any different?" After I got dressed, I got kissed and hugged by Rabbi Zedek and Cantor Friedman, paid my mikveh and mohel fees (not enormous by any means), and headed off with Ryan to Walker Bros. Original Pancake House to celebrate. Before leaving, I told Cantor Friedman that, in fact, I didn't feel different after mikveh. Maybe it was because I was in pain. Maybe it was because I already felt Jewish. I just didn't.

And then...

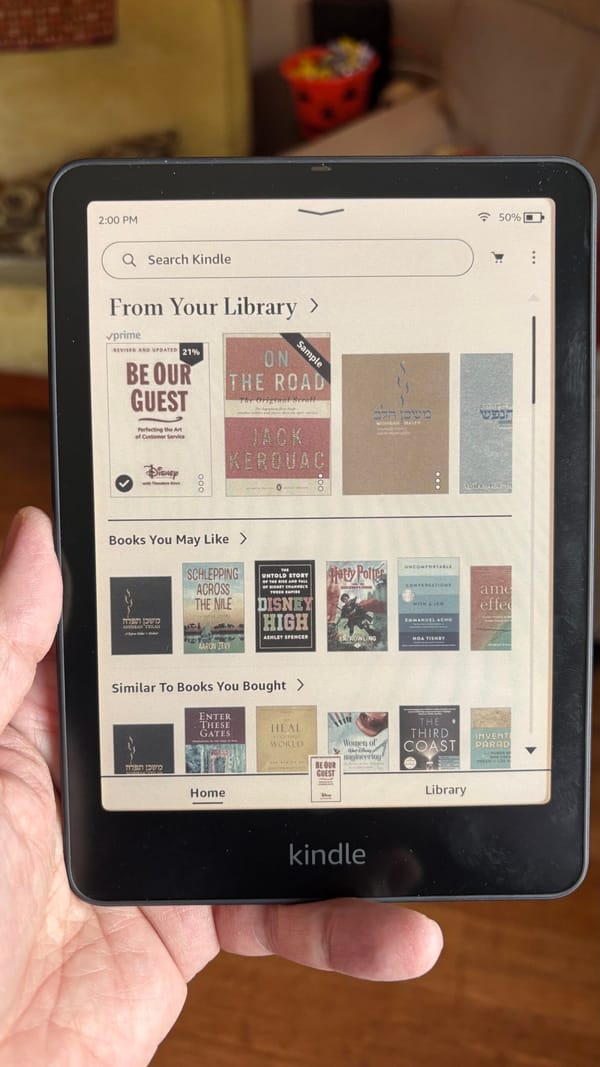

When the coffee came at Walker Bros., I raised the cup in my right hand and began to say a bracha...and realized I was a Jew saying his first bracha. I finished the bracha, sipped the coffee, and understood. I reached up to feel my kippah on my head, which it is my custom to wear at all times, and knew I was no longer a conversion candidate wondering if he was wearing his kippah correctly. I was, simply, a Jew wearing his kippah.

The realization made me almost leap out of my seat. It was such a subtle change, I hadn't felt it at the mikveh. But it was profound. It was like being a little kid on a bicycle who looks down and realizes his training wheels are gone, that he didn't notice when they fell away but he's still riding just fine. The realization grew for the rest of the day. On the bus. At 7-Eleven. At the Lincoln Park Zoo. Alone with Ryan. I wanted to look at my hands to see what a Jew looked like. I wanted to pinch myself. I was no longer converting. I would never be converting again. I was Jewish.

It was and is a feeling of exultant liberation. Of self-determination and, finally and at long last, ownership of my own Judaism. A conversion is a beginning, not an endpoint. There's a lifetime of Jewish knowledge yet to learn. But from here on out, I learn it as a Jew. Forever a Jew. Writing those words, if my laptop were not on my lap, I'd likely levitate out of my chair from the joy of it all. And from the gratitude for finally finding my soul's native adjective.

Not long after I sipped my coffee at the pancake house, Emanuel's famous rabbi emeritus, Rabbi Herman Schaalman, and his wife, Lotte, walked in and sat nearby. It was an amazing coincidence. (Truthfully, I know full well it was HaShem.) Before leaving, while Ryan paid the check, I went over to say hello. It turned out to be an auspicious day for the Schaalmans, as well. "We're beginning our anniversary celebrations," Rabbi Schaalman told me. "We've been married now for seventy years."

"I'm celebrating too," I said, beaming ear to ear. "I've been Jewish for an hour."

(Photo credit: KosherHam.com)