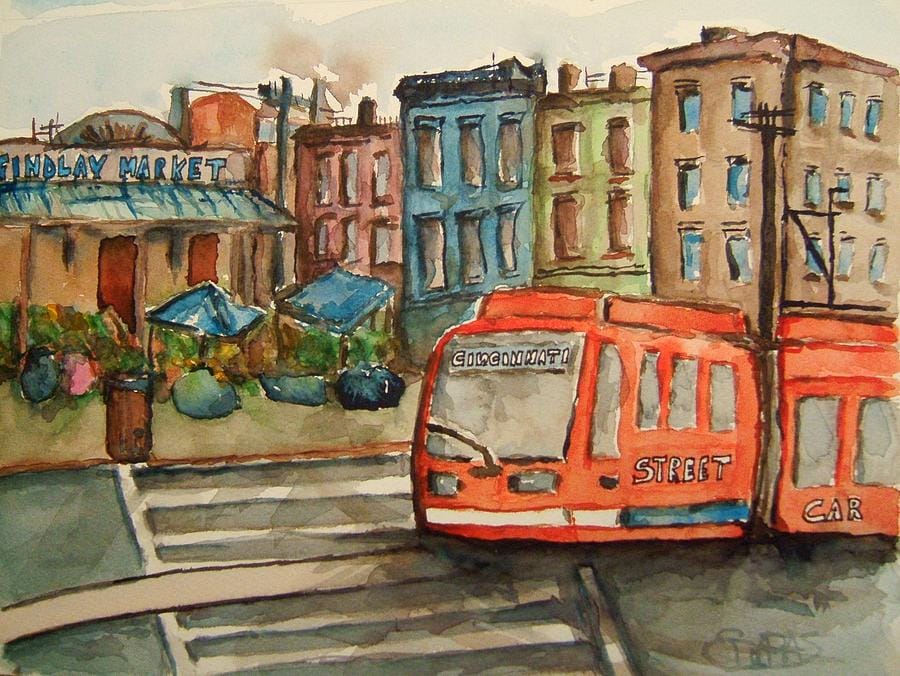

Cincinnati Is Cool, Part 2: The Streetcar Edition

In 2008, I wondered if up-and-coming Cincinnati's self-destructive strain of casual racism would ever be defeated. This month, that's exactly what happened.

Cincinnati is a town that always gets what it deserves, but not always in a good way. This month, Cincy got what it deserved the good way. After years of controversy and a last-minute attack by an anti-transit mayor, no further obstacles stand in the way of completing the city's streetcar transit project.

Some background is in order. Five and a half years ago I blogged that Cincinnati is Cool. The epic-length post chronicled my surprise during my first visit at how fun, interesting, urbane, and full of promise the place is in real life, and was widely read for months in the Queen City, itself.

In that post I noted Cincinnati's growing trend of liberal urbanism and hipness. But I also noted a disturbing counterpoint--an unrepentant insularity fed by decades as a conservative company town (Fifth Third Bank, Kroger, Macy's, Proctor & Gamble) that led residents immune to the city's hipness to feel at home openly expressing casual racism, classism, and anti-transit attitudes in public. In my 2008 post, I wondered which would win in the end: the forces trying to drag Cincinnati into 21st century America, or the forces trying to keep the city stuck in the 1950s.

Cincinnati's history might suggest the latter would win. After all, the city is home to the planet's largest unfinished subway system, partially built in the 1920s and then bricked over and abandoned before ever carrying a single rider. When the city began its streetcar project in the late 2000s as a tool to improve transit connectivity and attract more residents and businesses to its up-and-coming downtown core, many people expected the effort to meet a similar end.

Then a funny thing happened. The local hipsters found that a lot of other locals wanted light rail, too, including leaders in the city's supposedly stuffy business and foundation communities, and, eventually, outgoing African-American mayor Mark Mallory (I assure you his race is important) and a majority of City Council members. The city won $45 million in competitive funding from the Federal Transit Administration, and construction began.

And then a less funny thing happened. Conservative, anti-transit interests organized themselves politically and tried to kill the streetcar. They supported a new--and white (also important)--candidate when Mallory's term ended due to term limits and began a campaign to discredit the public funding of transportation projects. Incoming Tea Party mayor John Cranley won with a central campaign promise: stopping the streetcar project.

Here's the deal. "Anti-transit" in Cincinnati has nothing to do with transit or with the use of public funds for transit. The city has a sizeable and successful public bus system, complemented by bus systems on the Kentucky side of the Ohio River. "Anti-transit"--and its synonym, "anti-streetcar"--are nothing more than the linguistic version of white hoods worn over the heads of Queen City racists. They're fearful that the remnants of the African-American community in the city's downtown Over-the-Rhine neighborhood who have not yet been pushed out by gentrification will instead be carried to white corners of the city by a streetcar project whose main route goes right through OTR.

Which is a good thing. Everyone has a right to ride public transportation. And it isn't as if the city's existing bus system doesn't knit OTR together with the rest of the city already. No, today's anti-transit in Cincinnati simply means, "Let's keep the blacks in their place." In OTR. Which is part of an amazingly thriving and popular regional urban core. Except we don't know that because we've refused to set foot there for years.

Think I'm kidding? See here. And here. And here. And here. And here. And here. And here.

Or Google Cincinnati streetcar racism. Or more to the point, just Google Cincinnati racism.

Or travel back in time with me to the dinner I shared in downtown Cincinnati with three white acquaintances, one of whom felt perfectly free to opine in full voice that "Only the 'element' will ride the streetcar," as if even merely saying the words "African-American" was beneath him. And as if I, as a white person within earshot, would by definition find his choice of words acceptable.

Immediately after being sworn in on December 1st, Cranley engineered a City Council vote on pausing the streetcar project, pending a study to look at how expensive it would be to cancel the project. Cranley promised that the city could use any unspent FTA monies on other transportation projects. If the project continued, Cranley also demanded that operating expenses be paid for privately and not with public funds.

Of course, for the city to have gotten FTA funding, other cities had to go without. And to begin drawing down that funding, the city had already entered into a legal contract with the federal government. And public monies operate the existing bus system, and build and maintain the existing roadway system. And the major local foundations who would be instrumental in securing private operating monies were already threatening to pull money out of civic projects in protest over Cranley's streetcar opposition.

But, you know, details.

The City Council study found that it would cost Cincinnati more to end the streetcar project than to complete it. But that and the foregoing details weren't nearly as important as a letter Cranley received from the Federal Transit Administration, the details of which were widely reported in local media. The gist of the letter: complete the project or immediately pay us back $45 million.

The FTA reminded the city that the grant monies were a privilege received for a single purpose, and that the city was legally bound to proceed with the project. More importantly, the FTA said that if Cincinnati refused to repay the funds, federal funds destined for Cincinnati for other purposes would be frozen to make the debt whole. And it the most dramatic move of all, the FTA gave Cincinnati exactly one week to change its mind.

Cranley responded that the city would not be ordered around by the FTA. Then on December 19, the FTA letter's deadline day, a veto-proof City Council majority voted to continue and finish the streetcar project. Local foundation leaders promised to help find $900,000 in non-public monies every year for 10 years to get a swing vote needed to make the Council vote immune to Cranley's veto.

But unpacking that makes things even more interesting. Besides the fact that Cranley has probably broken the Queen City's speed record for becoming an abject mayoral failure, local foundation leaders don't actually have to disburse any monies until the streetcar starts operating in 2016, once the streetcar construction is completed. A lot can happen in three years--including changed financial priorities on the part of foundation and civic leaders. Meaning it's possible that annual $900,000 funding deal was nothing more than a convenient way to get Cranley out of the way.

If this were a Chicago story, I'd bet money on it.

The route that was the source of all the controversy was only the starter segment of a planned network of streetcars that, much like has happened so successfully in Los Angeles, would follow the city's original trolley corridors and work in tandem with the existing bus system to give the Queen City a modern, more useful transit system.

That sounds dry. The buried lede is the amazing urbanity, cultural richness, art, and liveliness of an urban core you've never visited but should. The streetwalls and lifelong residents of one of America's last architecturally unharmed, historic downtown neighborhoods. HighStreet. Park + Vine. The Aronoff Center. The Music Hall. Zaha Hadid's Contemporary Arts Center. Movies on Fountain Square on a warm summer night.

And a small but contentious number of residents who refuse to see the value in all of that. If they ever do, oddly enough, they'll probably find out riding the streetcar.